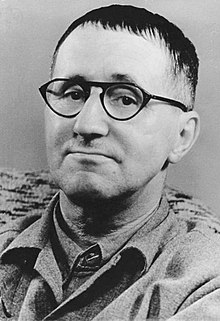

Bertold Brecht

| Bertolt Brecht | |

|---|---|

Bertolt Brecht

|

|

| Born | Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht 10 February 1898 Augsburg, Bavaria, German Empire |

| Died | 14 August 1956 (aged 58) East Berlin, East Germany |

| Occupation | Playwright, theatre director, poet |

| Nationality | German |

| Genre | Epic theatre · Non-Aristotelian drama |

| Notable works | |

| Spouses |

|

| Children |

|

|

|

|

| Signature | |

Eugen Bertolt Friedrich Brecht (/brɛkt/;German: [bʀɛçt]; 10 February 1898 – 14 August 1956) was a German poet, playwright, and theatre director of the 20th century. He made contributions to dramaturgy and theatrical production, the latter through the tours undertaken by the Berliner Ensemble – the post-war theatre company operated by Brecht and his wife, long-time collaborator and actress Helene Weigel.

Eugen Berthold Friedrich Brecht (as a child known as Eugen) was born in February 1898 in Augsburg, Bavaria, the son of Berthold Friedrich Brecht (1869–1939) and his wife Sophie, née Brezing (1871–1920). Brecht's mother was a devout Protestant and his father a Catholic (who had been persuaded to have a Protestant wedding). The modest house where he was born is today preserved as a Brecht Museum. His father worked for a paper mill, becoming its managing director in 1914. Thanks to his mother's influence, Brecht knew the Bible, a familiarity that would have a lifelong effect on his writing. From her, too, came the "dangerous image of the self-denying woman" that recurs in his drama. Brecht's home life was comfortably middle class, despite what his occasional attempt to claim peasant origins implied. At school in Augsburg he met Caspar Neher, with whom he formed a lifelong creative partnership. Neher designed many of the sets for Brecht's dramas and helped to forge the distinctive visual iconography of their epic theatre.

When Brecht was 16, the First World War broke out. Initially enthusiastic, Brecht soon changed his mind on seeing his classmates "swallowed by the army". Brecht was nearly expelled from school in 1915 for writing an essay in response to the line "Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori" from the Roman poet Horace, calling it Zweckpropaganda ("[cheap] propaganda for a specific purpose") and arguing that only an empty-headed person could be persuaded to die for their country. His expulsion was only prevented through the intervention of his religion teacher.

...

Wikipedia