Antiquities of Herculaneum

| |

| Original title | Antichità di Ercolano |

|---|---|

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Subject | Archaeology |

| Published |

1757–1792 (Charles VII of Naples) |

| Media type | |

| OCLC | 56782711 |

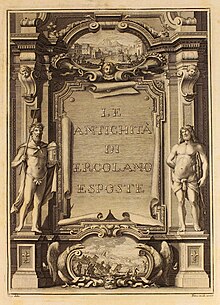

The Le Antichità di Ercolano Esposte (Antiquities of Herculaneum Exposed) is an eight-volume book of engravings of the findings from excavating the ruins of Herculaneum in the Kingdom of Naples (now Italy). It was published between 1757 and 1792, and copies were given to selected recipients across Europe. Despite the title, the Antichità di Ercolano shows objects from all the excavations the Bourbons undertook around the Gulf of Naples. These include Pompeii, Stabiae, and two sites in Herculaneum: Resina and Portici.

The engravings are high quality and the accompanying text displays great scholarship, but the book lacks the information on context that would be expected of a modern archaeological work. Le Antichità was designed more to impress readers with the quality of the objects in the King of Naples' collection than to be used in research. The book gave impetus to the neoclassical movement in Europe by giving artists and decorators access to a huge store of Hellenistic motifs.

The excavations at Heculaneum began in 1711, when a well was being dug for the new country house of Emmanuel Maurice, Duke of Elbeuf at Portici. The well turned out to have been sunk into the buried and richly ornamented proscenium of the theater of Herculaneum, and yielded several valuable marbles, including a statue of Hercules. The duke was extremely short of money. He smuggled the pieces to Rome to be restored, and then "gave" them to Prince Eugene of Savoy, his cousin. In 1738 Charles VII of Naples − after 1759, Charles III of Spain − began excavations to find objects for his private collection of antiquities, imposing tight security on the site. Interest was maintained by the hope of finding more objects of similar value to the first set of statues.

In 1739 a set of large mythical groups were found in the "Basilica". By 1748 the excavations had unearthed eight full-sized bronze statues. The large works were restored and put on display in the king's museum at Portici. The smaller works were generally not exhibited. The excavations were done by slaves, and it seems that much was destroyed or stolen. News of the finds spread, and Charles drew criticism for the secrecy and lack of science in the excavations.

...

Wikipedia