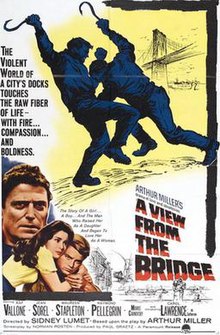

A View from the Bridge (film)

| A View from the Bridge | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Directed by | Sidney Lumet |

| Produced by | Paul Graetz |

| Screenplay by | Norman Rosten |

| Based on |

A View from the Bridge by Arthur Miller |

| Music by | Maurice Leroux |

| Cinematography | Michel Kelber |

|

Production

company |

Transcontinental Films

|

| Distributed by | Continental Film Distributors (US) |

|

Release date

|

19 January 1962 (France) 22 January 1962 (US) |

A View from the Bridge (French: Vu du pont, Italian: Uno sguardo dal ponte) is a 1962 French-Italian drama film directed by Sidney Lumet with a screenplay by Norman Rosten based on the play of the same name written by Arthur Miller.

It was filmed in English and French versions, and its exterior sequences were filmed on location on the waterfront of Brooklyn, New York, where the play and the film take place. Unlike the play, in which central character Eddie Carbone is stabbed to death with his own knife in a scuffle with his wife Beatrice's cousin Marco toward the end, in the film Eddie commits suicide by plunging a cargo hook into his chest.

The film was the first time that a kiss between men was shown on screen in America, in the sequence in which an intoxicated Eddie Carbone passionately kisses his wife Beatrice's male cousin Rodolfo in an attempt to demonstrate the latter's alleged homosexuality. However, this overture was intended as an accusation of someone being gay, rather than a romantic expression.

A View from the Bridge premiered in the United States on January 22, 1962, to generally negative reviews. In Film Quarterly, Pauline Kael called the film "not so much a drama as a sentence that's been passed on the audience."Stanley Kauffman's review for The New Republic was titled "The Unadaptable Adapted."

A more favorable review came from The New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther, who praised Sidney Lumet's realistic depiction of the Brooklyn waterfront and his choice of actors but believed that principal character Eddie Carbone lacked depth and dimension. "The rumbling and gritty quality of the Brooklyn waterfront," he wrote, "the lofty and mercantile authority of the freight ships tied up at the docks, the cluttered and crowded oppressiveness of the living rooms of the dockside slums are caught in his camera's comprehension, to pound it into the viewer's head that this is an honest presentation of the sort of personal involvement that one might watch—might spy upon—through a telescope set on Brooklyn Bridge." However, "The one great obstruction to the drama — and a fatal obstruction it becomes—is the slowly evolving demonstration that the principal character is a boor. As much as his nigh-incestuous passion and his subsequent jealousy may be credible and touching, they are low in the human emotional scale and are obviously seamy and ignoble. They haven't the universal scope of greed or envy or ambition or such obsessions as drive men to ruin."

...

Wikipedia