1971 San Fernando earthquake

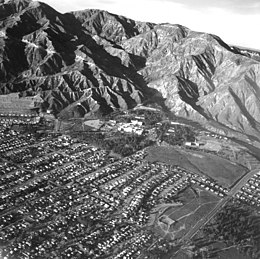

The San Gabriel Mountains with the Veterans Hospital complex in center

|

|

| Date | February 9, 1971 |

|---|---|

| Origin time | 06:00:41 PST |

| Duration | 12 seconds |

| Magnitude | 6.5–6.7 Mw |

| Depth | 13 km (8.1 mi) |

| Epicenter | 34°25′N 118°24′W / 34.41°N 118.40°WCoordinates: 34°25′N 118°24′W / 34.41°N 118.40°W |

| Type | Oblique-slip |

| Areas affected |

Greater Los Angeles Area Southern California United States |

| Total damage | $505–553 million |

| Max. intensity | XI (Extreme) |

| Peak acceleration | 1.25g at Pacoima Dam |

| Landslides | Yes |

| Casualties | 58–65 dead 200–2,000 injured |

The 1971 San Fernando earthquake (also known as the Sylmar earthquake) occurred in the early morning of February 9 in the foothills of the San Gabriel Mountains in southern California. The unanticipated thrust earthquake had a moment magnitude of 6.5 or 6.7 (as determined by several independent institutions) and had a maximum Mercalli intensity of XI (Extreme). The event was one in a series that affected the Los Angeles area in the late 20th century, and a study of the Sierra Madre Fault during that time indicated that more substantial thrust earthquakes had occurred near the Transverse Ranges in the past. Damage was locally severe in the northern San Fernando Valley, and surface faulting was extensive to the south of the epicenter in the mountains, as well as urban settings along city streets and neighborhoods. Uplift and other effects affected private homes and businesses.

The event affected a number of health care facilities in Sylmar, San Fernando, and other densely populated areas north of central Los Angeles. The Olive View Medical Center and Veterans Hospital both experienced very heavy damage, and buildings collapsed at both sites, causing the majority of deaths that occurred. The buildings at both facilities were constructed with mixed styles, but engineers were unable to thoroughly study the buildings' responses because they were not outfitted with instruments for recording strong ground motion, and this prompted the Veterans Administration to install seismometers at its high-risk sites. Other sites throughout the Los Angeles area had been instrumented as a result of local ordinances, and an extraordinary amount of strong motion data was recorded, more so than any other event up until that time. The success in this area spurred the initiation of California's Strong Motion Instrumentation Program.

Transportation around the Los Angeles area was severely afflicted with roadway failures and the partial collapse of several major freeway interchanges. The near total failure of the Lower Van Norman Dam resulted in the evacuation of tens of thousands of downstream residents, though an earlier decision to maintain the water at a lower level may have contributed to saving the dam from being overtopped. Schools were affected, as they had been during the 1933 Long Beach earthquake, but this time amended construction styles improved the outcome for the thousands of school buildings in the Los Angeles area. Another aspect of the event were the hundreds of various types of landslides that were documented in the San Gabriel mountains. As had happened following other earthquakes in California, legislation related to building codes was once again revised, with laws that specifically addressed the construction of homes or businesses near known active fault zones.

...

Wikipedia