1863 New York City draft riots

| New York City draft riots | |

|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |

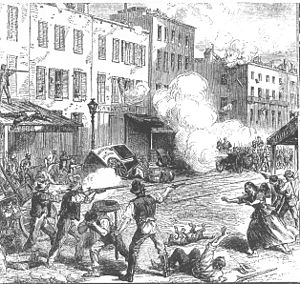

A drawing from a British newspaper showing armed rioters clashing with Union Army soldiers in New York City.

|

|

| Date | July 13, 1863 – July 16, 1863 |

| Location | Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Result | Riots ultimately suppressed |

| Casualties | |

| Death(s) | 119–120 |

| Injuries | 2,000 |

The New York draft riots (July 13–16, 1863), known at the time as Draft Week, were violent disturbances in Lower Manhattan, widely regarded as the culmination of working-class discontent with new laws passed by Congress that year to draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War. The riots remain the largest civil and racial insurrection in American history, aside from the Civil War itself.

U.S. President Abraham Lincoln diverted several regiments of militia and volunteer troops from following up after the Battle of Gettysburg to control the city. The rioters were overwhelmingly working-class men, who resented that wealthier men, who could afford to pay a $300 (equivalent to $9,157 in 2017) commutation fee to hire a substitute, were spared from the draft.

Initially intended to express anger at the draft, the protests turned into a race riot, with white rioters, predominantly Irish immigrants, attacking blacks throughout the city. The official death toll was listed at either 119 or 120 individuals. Conditions in the city were such that Major General John E. Wool, commander of the Department of the East, said on July 16 that "Martial law ought to be proclaimed, but I have not a sufficient force to enforce it."

The military did not reach the city until after the first day of rioting, by which time the mobs, primarily ethnic Irish, had already ransacked or destroyed numerous public buildings, two Protestant churches, the homes of various abolitionists or sympathizers, many black homes, and the Colored Orphan Asylum at 44th Street and Fifth Avenue, which was burned to the ground.

The area's demographics changed as a result of the riot. Many blacks left Manhattan permanently (many moving to Brooklyn). By 1865 their population fell below 10,000, the number in 1820.

New York's economy was tied to the South; by 1822 nearly half of its exports were cotton shipments. In addition, upstate textile mills processed cotton in manufacturing. New York had such strong business connections to the South that on January 7, 1861, Mayor Fernando Wood, a Democrat, called on the city's Board of Aldermen to "declare the city's independence from Albany and from Washington"; he said it "would have the whole and united support of the Southern States." When the Union entered the war, New York City had many sympathizers with the South.

...

Wikipedia