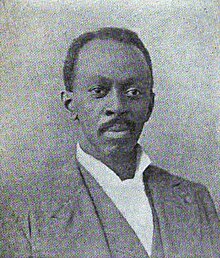

Richard R. Wright

| Richard Robert Wright Sr. | |

|---|---|

Richard R. Wright

|

|

| President of Georgia State Industrial College for Colored Youth | |

|

In office 1891–1921 |

|

| Succeeded by | Cyrus G. Wiley |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

May 16, 1855 Dalton, Georgia |

| Died | July 2, 1947 (aged 92) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Spouse(s) | Lydia Elizabeth (Howard) Wright |

| Alma mater |

Atlanta University The Wharton School |

| Profession | American military officer, educator, banker |

Richard Robert Wright, Sr. (May 16, 1855 – July 2, 1947) was an American military officer, educator and college president, politician, civil rights advocate and banking entrepreneur. Among his many accomplishments, he founded a high school, a college and a bank. He also founded the National Freedom Day Association.

Wright was born into slavery on May 16, 1855, in a log cabin six miles from Dalton, Georgia.

After emancipation, Wright’s mother moved with her son from Dalton to Cuthbert, Georgia. He attended the Storrs School. The school had a reputation among freedmen as a place for their children to be educated. While visiting the school, retired Union General Oliver Otis Howard asked what message he should take to the North. The young Wright reportedly told him, "Sir, tell them we are rising." That exchange inspired a once-famous poem by John Greenleaf Whittier.

The Storrs School, a forerunner of Atlanta University, was one of many academic schools for freedmen's children founded by the American Missionary Association (AMA). He was valedictorian at Atlanta University's first commencement ceremony in 1876.

In 1890, Emanuel K. Love and Wright were in a dispute with William White, Judson Lyons, Henry Rucker, and especially John H. Deveaux, who was in control of Georgia's African American Republic Party machinery. The dispute centered around leadership of the party district nomination conventions. Lyons, Rucker, and Deveaux were all supported by patronage of Booker T. Washington of the Tuskegee Institute and were identified with light-skinned elites, while Love and Wright (and Charles T. Walker) represented a "black" or "darker-skinned" faction, although skin color was not as important as political allegiance and ideology.

...

Wikipedia