Bibliography of Ulysses S. Grant

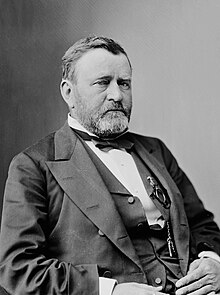

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822 – July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States (1869–1877) following his success as military commander in the American Civil War. Under Grant, the Union Army defeated the Confederate military; the war, and secession, ended with the surrender of Robert E. Lee's army at Appomattox Court House. As president, Grant led the Radical Republicans in their effort to eliminate vestiges of Confederate nationalism and slavery, protect African American citizenship, and defeat the Ku Klux Klan. In foreign policy, Grant sought to increase American trade and influence, while remaining at peace with the world. Although his Republican Party split in 1872 as reformers denounced him, Grant was easily reelected. During his second term the country's economy was devastated by the Panic of 1873, while investigations exposed corruption scandals in the administration. The conservative white Southerners regained control of Southern state governments and Democrats took control of the federal House of Representatives. By the time Grant left the White House in 1877, his Reconstruction policies were being undone. After leaving office, Grant embarked on a two-year world tour that included many enthusiastic receptions. In 1880, he made an unsuccessful bid for a third presidential term. However, his memoirs, written as he was dying, were a critical and popular success, and his death prompted an outpouring of national mourning. Historical assessments of the Grant Administration have traditionally been critical; Grant's presidency having been ranked among the lowest by historians. Grant's reputation was marred by his defense of corrupt appointees and by his conservative deflationary policy during the Panic of 1873. While still below average, his reputation among scholars has significantly improved in recent years because of greater appreciation for his commitment to civil rights, moral courage in his prosecution of the Ku Klux Klan, and enforcement of voting rights.

...

Wikipedia